- CybAfrique Newsletter

- Posts

- Meta’s guide to ethical moderation

Meta’s guide to ethical moderation

also ft infosec in times of crises and other infosec news from Africa

CybAfriqué is a space for news and analysis on cyber, data, and information security on the African continent.

HIGHLIGHTS

Meta’s guide to ethical moderation

There are, let's say, two and a half ways to block a social media account, and the difference between them tells a complicated story about who exactly runs the world now. The canonical, big-league case everyone knows is, of course, the one about the former US President, Donald Trump. Meta, acting as a private, quasi-sovereign entity, decided his posts violated their Community Standards against inciting violence. It was a messy, ethics-heavy decision, but it was driven by the corporation's internal rules. This is the first kind of block, where a company decides that the user has violated their terms of service and, therefore, deplatforms them.

But there are smaller, more terrifying ones, especially across Africa. This brings us to Africa.

In the wake of a contested election in Tanzania and calls for protests, Meta blocked accounts of two prominent critics of the government: Mange Kimambi and Maria Sarungi-Tsehai.

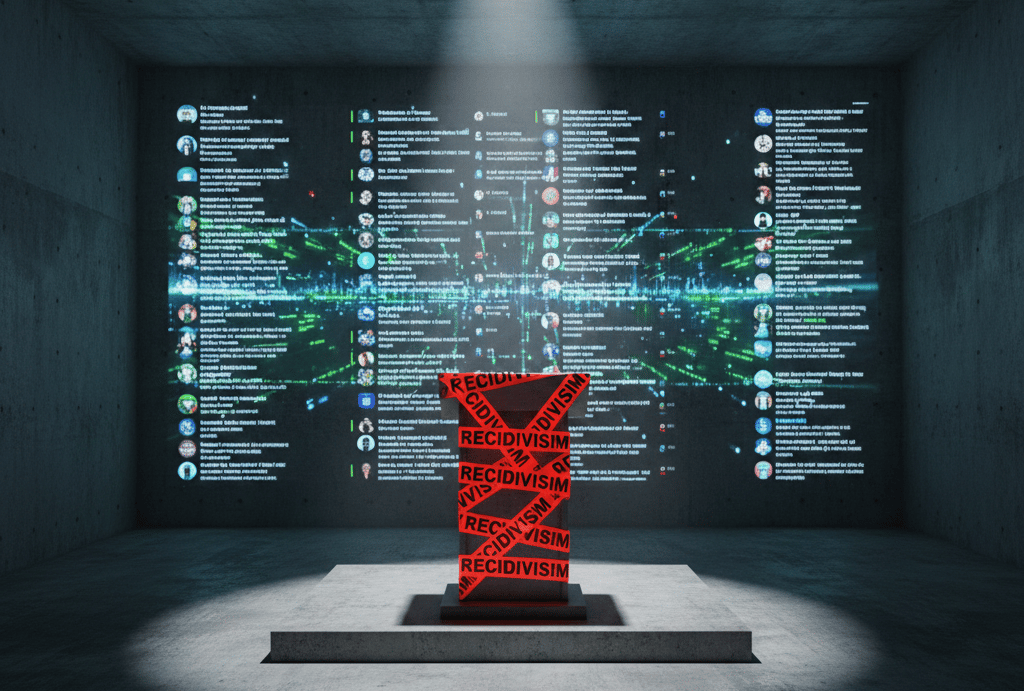

One of the activists, Mange Kimambi, had her account banned for violating Meta’s recidivism policy, which is essentially a tougher Community Standard enforcement for repeat offenders. This is an Internal Ethics Block again, but the context, following an election crisis, makes it feel more fraught. Was the recidivism policy applied because of political pressure, or genuinely because her content violated rules?

The other activist, Maria Sarungi-Tsehai, had her Instagram account blocked following a legal request from Tanzanian authorities. That is the second, and arguably more dangerous, kind of block.

Meta confirmed it restricted access to Sarungi-Tsehai's account in response to regulatory demands. Since the early 2020s, bodies like Meta and TikTok have increased cross-collaboration with government bodies, both for data requests (which are still relatively low in Africa compared to the US) and content takedowns. This has been useful in areas like combating child sexual abuse material (CSAM) and coordinating counter-terrorism content, but it has also opened ground for digital repression like this.

The core dilemma, as always, is threading the needle between global human rights principles and local law compliance. Organizations like Access Now push Meta to adhere to its publicly stated commitments, like those with the Global Network Initiative, which requires companies to push back against government requests that violate human rights. This is less "law" and more "accountability for your own written policies."

The way these companies have to thread this ethic of blocking accounts, and also, how to cooperate with governments without enabling crackdowns, comes down to the same old, boring advice: better governance and better transparency.

Infosec during times of crisis

We’ve been asking ourselves what infosec should look like in times of crisis, courtesy of reports on cases of increased SIM swapping fraud in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a country currently fighting a civil war.

Infosec is often connected to, and often worsened during crises. Somehow, it is simultaneously deprioritized — because who cares about phishing attacks when a militia is on the doorstep?

In places like Goma and Bukavu, when fighting has caused banks to close, mobile money has become practically the only way to transact, a financial system that’s constantly threatened by SIM swapping fraud, enabled by low literacy rates, poor KYC policies, and corruption.

A similar case was recorded in Sudan when both the Sudanese army and RSF destroyed communication infrastructure, used spyware, and weaponized data denials.

We've been asking why information security takes a backpedal during a crisis. It's usually deprioritized for obvious reasons: physical safety comes first. But our case studies show that the deprioritization of infosec rights often worsens overall security. They often enable mass fraud, hamper humanitarian efforts, and cause digital regression.

FEATURE

A lot is at stake as Nigeria’s National Identity Management Commission (NIMC) attempts a migration to MOSIP, the open-source digital identity platform backed by the World Bank and the Gates Foundation. Read here.

HEADLINE

Government proposes new spectrum sharing rule for telcos under new rules

Unlocking the threat: card fraud undermines digital progress for the majorityity in South Africa

Ethiopia showcases rapid tech and startup growth at 4th african startup conference

GEFONA's response to AUC's consultation on africa data policy framework

ACROSS THE WORLD

IMAGE OF THE WEEK

See you next week.

Reply