- CybAfrique Newsletter

- Posts

- Over-the-counter spyware in Kenya

Over-the-counter spyware in Kenya

also ft infosec and bureaucracy; and other infosec news from across Africa

CybAfriqué is a space for news and analysis on cyber, data, and information security on the African continent.

HIGHLIGHTS

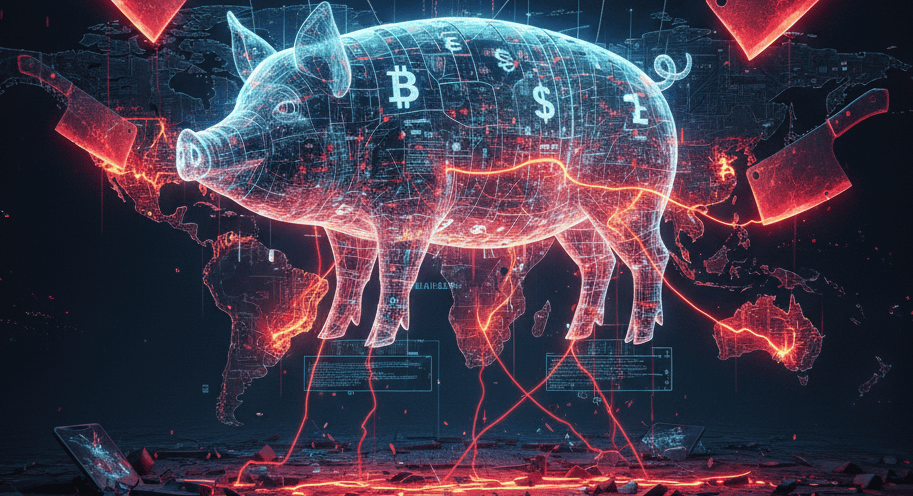

A brief history of pig butchering scams

Earlier this year, we covered the arrest of 800 suspects at a pig butchering scam center in Lagos. We covered this as the first known case of pig butchering in an African country. We were wrong. There have been at least three other busts across the continent in Namibia, Zambia, and Angola, although with far smaller numbers of arrests. There

All cases feature arrests of mainly Chinese nationals as syndicate leaders. This is interesting. Pig butchering is considered almost native to Southeast Asia, but it’s actually not. Pig butchering is a Chinese invention, named originally as Sha Zhu Pan. The fraud model was perfected by Chinese criminal organizations, who initially targeted Mandarin speakers. When mainland crackdowns started in the 2010s, they began outsourcing operations to Southeast Asia. This migration also led to the popularization of pig butchering in Southeast Asia, with hotspots like Myanmar.

Now, the second wave of crackdowns in places like Myanmar is forcing a second, dramatic relocation. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), in its report Inflection Point, documented this geographic shift. According to their April report, Chinese and Southeast Asian criminal gangs, responsible for generating tens of billions of dollars annually from these schemes, are aggressively expanding globally after being displaced in Southeast Asia.

Africa has become a promising target in that expansion. Scam syndicates thrive on certain socioeconomic factors. It needs a talent pool, often a large, primarily young, English (or more recently French)-speaking population, regulatory gaps, and some form of local network and expertise. All of this, you can argue, is present on the African continent.

The Nigerian Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) noted some collaboration. During the Lagos raid, the commission found facilities resembling corporate headquarters equipped with high-end desktop computers used to train hundreds of accomplices.

The EFCC Executive Chairman, Ola Olukoyede, said, “Foreigners are taking advantage of our nation's unfortunate reputation as a haven of fraud to establish a foothold here to disguise their atrocious criminal enterprises,” as covered by The Times.

Bureaucracy and infosec

Africa’s pursuit of information security and digital rights is often mediated, and sometimes mutilated, by bureaucracy. This friction defines the current era of Africa’s digital renaissance, with state processes acting as both essential architects and potent inhibitors of digital freedoms. To understand this dynamic, we can examine a singular, enduring case study: the creation and subsequent weaponization of Uganda’s National Identification and Registration Authority (NIRA).

The initial rationale for NIRA and the NIN system was soundly bureaucratic and ostensibly beneficial for infosec. The goal was to establish a single, reliable source of identity (ID) for all citizens, eliminating fraudulent registrations, secure transactions, and e-citizenship.

This is nice. An infosec expert might argue that a robust, accountable ID system is the most important piece of national security infrastructure, allowing the government to implement stringent, transparent security standards from the top down, but NIRA’s implementation swiftly revealed how bureaucracy quickly turns security into control.

The mandatory NIN-SIM linkage provides the state with a real-time surveillance capability. This power was soon deployed through bureaucratic directives that routinely violate established digital rights norms, like mass disconnections and targeted surveillance.

“Across the continent, there have been reports of strenuous and sometimes unclear demands by states on intermediaries, including facilitating interception of communication, disclosing communication data of their subscribers to state security agencies, and taking down content or shutting down the internet. In countries such as Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, legal provisions requiring mandatory compliance by third parties to government interception requests have been introduced, undermining civic freedoms,“ reports CIPESA.

In the NIRA case, the state does not even need to make demands on intermediaries; the bureaucracy has compelled the intermediaries (telecoms) to link the identity data directly to the state registry, creating a surveillance framework by design.

When bureaucracy focuses on standards, accountability, and legal clarity (e.g., establishing the mechanism for secure IDs), it betters infosec and digital rights. When it prioritizes centralized control and political expediency (e.g., mandatory, rights-violating linkage and arbitrary disconnections), it becomes the single greatest amplifier of digital insecurity and the most effective tool for eroding digital rights.

Africa’s digital renaissance depends heavily on this balancing act. Building the necessary bureaucratic infrastructure is important, as is the political independence and legal transparency of these institutions.

FEATURES

HEADLINES

Algeria launches 5G, grants licenses to 3 national operators

The R44.2m click: why human error is South Africa’s biggest cyber threat

Protecting electoral integrity against AI-Driven disinformation

HOLIDAY FRAUD! festive season sparks mobile money crime wave

What cyber attacks on Ethiopian government tell us about the future of armed conflict in Africa

African cybercrime forum in Kenya: authorities cite alarming figures

ACROSS THE WORLD

OPPORTUNITIES

See you next week.

Reply